Photos divers

|

Suite

|

Suite

|

Square BIRTZ en 1940

|

Square BIRTZ en 2001

|

Suite

|

Lac Birtz

|

Lac Birtz

|

Lac Birtz

|

Rue Birtz

|

Lettre

|

Timbre poste

|

Timbre poste

|

Journeaux

|

Etienne Birtz 1730-1786ll est le fils d'Adrien Birtz, maréchal ferrant,et de Marguerite Neveu. Les origines de son patronyme sont à rechercher en Belgique et notamment dans le pays de Liège, lieu de naissance de son grand père. L'enfance d'Etienne se déroule dans un climat politique orageux. A cette époque, la France est en guerre avec la plupart de ses voisins et a constamment besoin de nouvelles recrues dans ses armées. Sur la place publique, on bat le tambour, on affiche des placards, on convoque tous les hommes valides dont l'âge varie de 20 à 30 ans. La future recrue tire un jeton : un blanc et il est exempté, un noir et il est mobilisé sur le champ pour six ans. Dès lors, on exige la signature du "volontaire". C'est dans ce contexte que le 14 janvier 1752, àl'àge de 22 ans, le sieur Birtz est enrôlé au sein du régiment de Béarn. Le registre d'inscription porte quelques informations supplémentaires : son surnom ou nom de guerre est Démarteau, sa taille est de 1m64 et son métier est maréchal-ferrant. Son profil s'avère un précieux atout pour l'officier chargé de sélectionner son effectif militaire, surtout lors de la levée d'unê nouvelle compagnie. En effet Etienne possède déjà la maîtrise de la taillanderie et de la maréchalerie, métiers artisanaux, traditionnellement basés sur la science compagnonnique européenne. A la fin de l'année 1754, l'Angleterre décide d'envoyer des troupes en Amérique pour y soutenir ses colons. lnformé, Louis XV décrète l'envoi en Nouvelle-France de 3.600 hommes ainsi qu'une grande quantité de matériels et d'armements en vue de défendre ses possessions. Six bataillons sont tirés au sort et celui d'Etienne Birtz en fait parti. Ces bataillons se dirigent alors vers la Bretagne et le sieur Birtz stationne à Morlaix du 2 au 4 awil1755. Le 8 avril 1755, son régiment se rend à Brest où est amarrée une escadre composée de 13 vaissêaux et 3 frégates. A cette occasion les troupes sont équipées de nouveaux habits (mais délivrés après leur débarquement) et dês fusils du modèle 1746, visiblement mal entretenus et mal conservés. L'animation est de plus en plus intense dans Ia ville où tout laisse présager un convoi en partance...On aperçoit dans les rues et les tavernes du port un nombre croissant de soldats. Mais cette effervescencê est de courte durée car les régiments sont prêts et embarquent dans la foulée. Le sieur Birtz se trouve sur Le Léopard, vaisseau de 64 canons, réduit à 22 pièces pour charger du fret. Pendant 25 jours, la flotte reste en rade contrariée par les vents. Le général donne enfin I'ordre d'appareiller dans Ia matinée du 3 mai et les navires commencent à faire route sous une escorte chargée de les protéger jusqu'à la haute mer. Après une traversée de 51 jours à travers l'Océan Atlantique, le Léopard mouille dans la rade de Québec le 23 juin au matin. Le lendemain, le commissaire provincial des guerres fait débarquer les compagnies qui sont logées chez I'habitant. Quelques jours plus tard, le commandant de Béarn ordonne le départ de son bataillon qui se met alors en route pour Montréal en remontant le fleuve St Laurent. En mai 1756, la guerre de Sept-Ans (1756-1763), première à l'échelle mondiale, est officiellement déclarée. Etienne participe, de façon très active, à toutes les campagnes que mène son régiment durant ce conflit. Dans un premier temps, il piend part à l'attaque de Fort Oswégo, une base britannique d'environ 1000 hommes. La bataille, rassemblant 3.000 soldats français, se solde par la prise du fort par les Franco-Canadiens. Après avoir passé l'hiver dans ses quartiers, le détachement de Béarn participe à l'assaut de Fort Gêorge dès lévrier 1757. La mission échoue et les troupes reviennent à Montréal. C'est à l'occasion de ce retour, et plus précisément le 18 avril 1757, que le sieur Birtz se marie avec Marguerite Robert à St Famille Boucherville (Québec). Accolé à son acte de mariage, on lui accorde un bail verbal sur un lopin de terre situé près de l'église où il crée sa boutique de maréchal ferrant et y exerce partiellement son métier jusqu'au temps de sa démobilisation (1760). En effet les lnstructions du Roi de 1755 donnent la permission aux soldats de s,établir en Nouvelle-France, soit bour y défricher des terres ou pour y exercer des métiers utiles dont on manquerait. Ce faisant, on leur accorde la permission de se marier dans la colonie, pourvu que ces mêmes soldats y terminent leur service militaire jusqu,au temps du retour de leur corps de troupe en France. Quatre mois après ses noces, les combats reprennent pour Ie sieur Birtz. Les français réattaquent et capturent le Fort Georgê. L'année suivante, Etienne combat à Fort Garillon où 15.ooo anglais essayent, sans succès, d'emporter d'assaut les fortifications improvisées avec des arbres abattus et défendues seulement par les 3.500 hommes de Montcalm. Au début 1259, son bataillon est affecté à la force principale de défense de Québec où les Anglais forcent Montcalm à livrer bataille aux portes de Ia ville. Le régiment de Béarn était au centre de la ligne de bataille. Cet affrontement se solde par l'écrasante défaite française et la mort de ses 2 généraux: wolfe et Montcalm. Quelques jours plus tard la ville de Québec capitule après 2 mois de combat. Les troupes retournênt à Montréal pour I'hiver. Mais, durant la guerre, la vie d'Etienne continue. Ce dernier fait l'acquisition d'un emplacement dans le bourg de Boucherville, le I avril 1760, pour la somme de 3.600 livres dont 2.400 furent remises auxdits vendeurs "en plusieurs bonnes ordonnances du Trésor, argent du pays." Gette bonne somme d'argent devait sûrement être le fruit d'un bon troc de fourrures fait, soit au fort Frontenac en 1755, ou encore à carillon en 1758. En effet ces soldats "artisans du fer", venus de France, sont attirés par le commerce des fourrures. Outre la réparation des armes et des outils dans les forts de défense et de traite, ils s'adonnent au négoce avec les Amérindiens. Avec eux, ils troquent ces mêmes fourrures contre de la poudre de fusil, des objets de fer, pièces de vêtements ou simplement de la nourriture. Au cours du même mois d'avril, Etienne Birtz reprend les armes à la campagne de Ste Foy (à proximité de Québec) où les français font le siège de la ville. Mais l'arrivée de frégates anglaises oblige l'armée à battre en retraite vers Montréal ou, le I septembre, le gouverneur du Canada capitule face au siège britannique imminent. En novembre, la majorité des troupes françaises, non mariée aux femmes canadiennes, retourne vers la France et le traité de Paris, signé le 10 février 1763, rend définitivement le Ganada à l'Angleterre. Etienne Birtz ne repart pas vers Ie Royaume de France. Par sa détermination, Etienne satisfait pleinement aux conditions prescrites par Ie Roi et, avec le consentement de ses supérieurs, il peut donc s'établir en permanence au Ganada. Le sieur Birtz b'installe ainsi définitivement avec sa femme à Boucherville où il a installé sa boutique de maréchal ferrant 3 ans auparavant et qui se caractérise par l'enseigne de deux marteaux croisés. Dès lors, son activité de forgeron et sa vie de famille constituent son quotidien. En 1768, le sieur Birtz fait l'acquisition d'une seconde demeure. En contrepartie d'une rente viagère, Pierre Robert, son beau-père, lui abandonne une métairie située "au pays Brulé" sur laquelle il y'a "une Bonne Maison Biens Laujable ..., une grange en Bonne ordre ..., une bonne Escury ..., une Estable." Des démêlés judiciaires s'ensuivirent à ce sujet, La métairie demeure en possession d'Etienne jusqu'en 1781, date à laquelle elle devient la propriété de Louis Gicot. En 1777, Etienne procède à la vente de son emplacement situé au bourg de Boucherville "avec boutique attenante" pour la somme de 1.200 livres. A cette époque, la guerre de l'lndépendance Américaine (1775-17831 engendre une sévère crise économique, non seulement sur le malché canadien des fourrurés, mais aussi sur la dévalorisation de la Livre Sterling. C'est pourquoi Etienne cumula une perte de 2.400 livres face à l'achat qu'il en avait fait le 8 avril 1760. Le 4 août 1786, à Boucherville, Etienne Birtz s'éteint à l'âge de 56 ans. Trois mois plus tard, un inventaire après décès est effectué par le notaire Racicot. Cet inventaire prouve qu'il s'occupait activement de négoces liés à la traite des fourrures. Le montant de ses créances s'élève à 1.388 livres et ne concerne que des dettes contractées avec des marchands-équipeurs, des engagistes, des négociants, incluant le capitaine de milice de l'époque. L'estimation de ses biens ne s'élevant qu'à 3OO livres, les héritiêrs légaux n'ont eu d'autres choix que de renoncer à la succession. En laissant derrière lui 9 enfants, I'histoire d'Etienne Birtz survécut aux affres du temps. Notre soldat émérite assura la succession du patronyme Birtz en Amérique du Nord à travers les siècles scellant à jamais son histoire et les liens qui unissent cette famille à notre village. Parmi ses nombreux descendants, un homme mérite d'être cité pour ses exploits sportifs accomplis lors de compétitions internationales. ll s'agit d'Etienne Desmarteau (1873-1905), policier à Montréal qui s'est illustré comme étant le 1"'canadien médaillé d'or lors des Jeux Olympiques de Saint Louis en 1904 au lancer de poids. Par ses performances, ce champion olympique permit de faire connaître mondialement un patronyme derrière lequel se cache l'histoire inhabituelle d'un soldat français durant la Guerre de Sept Ans. Sources: - Archives Départementales de la Moselle (Metz) - Archives Nationales du .Québec (Montréal) - Collection Lévis, 12 volumes. - Comte Maurès de Malartic. Journal des Campagnes au Canada de 1755 à 1760. - Kunster, Maillard et Montgredien, Les régimenE sous Louis XIV et Louis XV. - Service Historique des Armées de Terre (Vincennes) Recherche et rédaction effectuées par Gilles BIRTZ (Québec) et Florent PIERRON. 2000 - 2004 Florent PIERRON |

Archives Montreal Quebec Canada

|

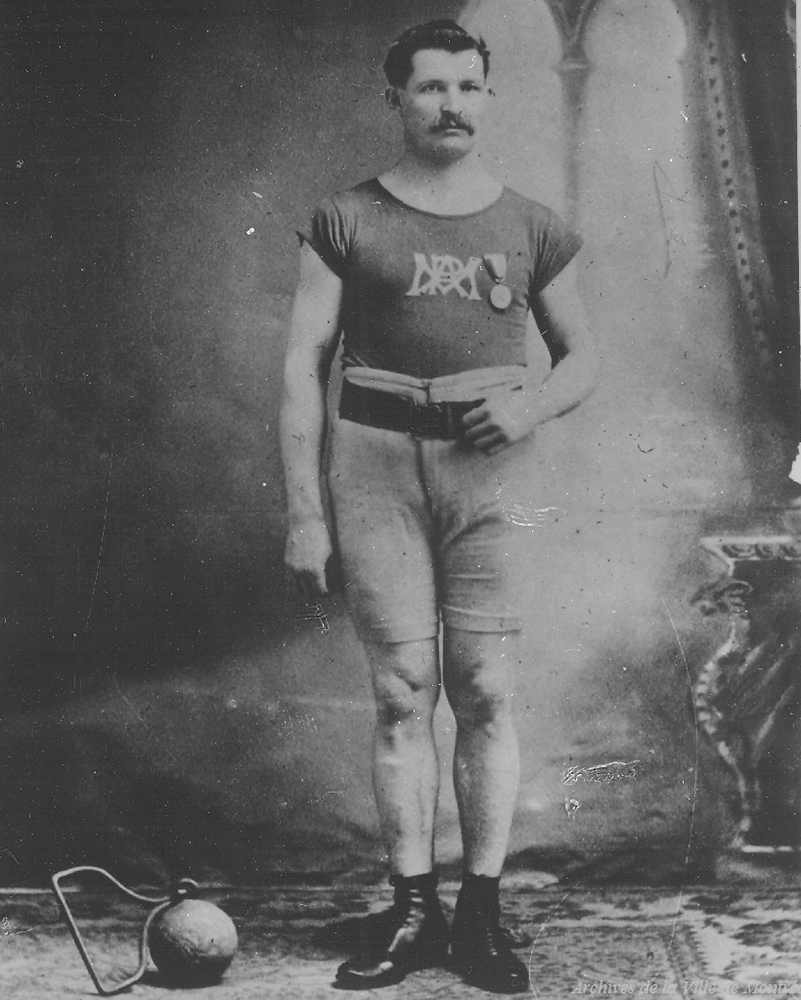

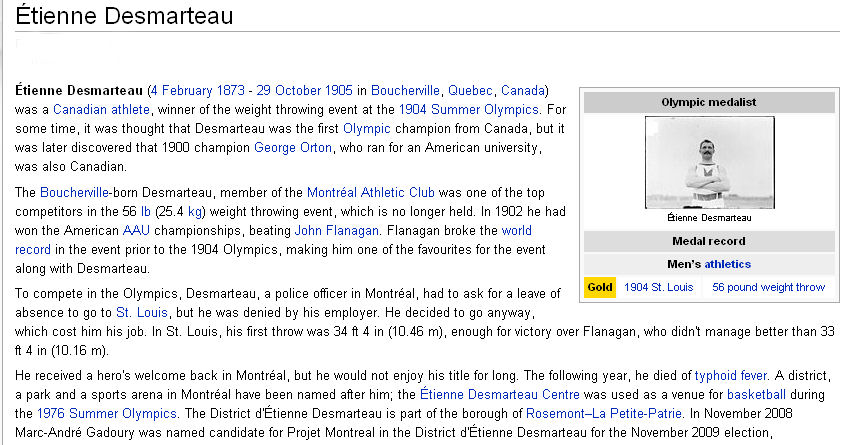

Etienne Desmarteau Photo d'Étienne Desmarteau (1873-1905), un athlète montréalais de renom. D'abord ouvrier chez la Canadian Pacific Foundry, Desmarteau entre dans les forces policières de la ville en 1901. C'est là qu'il se fait remarquer par la Montreal Amateur Athletic Association pour sa rapidité et sa force. Il gagne alors plusieurs championnats d'athlétisme et, en 1904, il remporte la médaille d'or pour le lancer du poids de 56 livres aux Jeux olympiques d'été de Saint-Louis aux États-Unis. Il devient ainsi le premier Canadien français gagnant d'une médaille d'or olympique. Desmarteau est intronisé au Temple de la renommée olympique du Canada en 1949 et l'on donne son nom à un centre sportif construit en vue des Jeux olympiques de Montréal en 1976. |

|

From Dictionary of Canadian Biography Online

DESMARTEAU, ÉTIENNE (baptized Joseph-Étienne Birtz), labourer, policeman, and athlete; b. 4 Feb. 1873 in Boucherville, Que.

, son of Étienne Birtz, a farmer, and Caroline Dubuc; d. unmarried 29 Oct. 1905 in Montreal, and was buried on 31 October

in Boucherville. The first member of the Birtz family to come to New France arrived around 1750 with the Régiment de Béarn.

After the conquest of the colony by Great Britain, this Étienne Birtz resumed his trade as a blacksmith. Since his shop

was marked by a sign bearing two crossed hammers, he was given the name Desmarteaux. In place of the plural form, his

descendants preferred the singular, Desmarteau. After Étienne Desmarteau, the second of seven children, was born, the

family left Boucherville and moved to Montreal. Étienne does not seem to have been fond of attending school when he was

young. Later he was employed by the Canadian Pacific Railway as a metal-caster and then in 1901 he became a policeman in

Montreal. Six feet tall and weighing 208 pounds, he distinguished himself by two known acts of bravery. The first occurred

in 1902, when he arrested someone preparing to set fire to a store in which there were four young children and their parents.

The second came in 1905, when he arrested a thief presumed to be dangerous. Desmarteau was considered a model policeman,

always on good terms with his colleagues. He was sometimes sharp-tongued, however, as can be seen by the complaint brought

against him in 1905 after a demonstration during which he reportedly hurled abuse at one of his superiors

Desmarteau went down in history because of his physical strength. In 1902 he ranked first in the world junior and heavyweight hammer-throwing championships. But he is remembered for his victory at the 1904 Olympics in St Louis, Mo., when he managed a throw of 34 feet 4 inches in the 56-pound weight contest. He was long regarded as the first Canadian to have earned a gold medal, although not all experts agree. Some claim the honour belongs to George Orton, who had won the 2,500-metre steeplechase in Paris four years earlier. Orton, a Canadian by birth, was, however, wearing the colours of the United States, where he was studying. Others maintain that Desmarteau should be considered the first since George Seymour Lyon’s victory in the golf competition at St Louis in 1904 ought to be disregarded, golf having been included in the Olympic Games only that one time. In any case Étienne Desmarteau certainly was the first French Canadian to receive an Olympic gold medal. Desmarteau nearly missed his date with fame, when permission to participate in the St Louis games was refused him by the Montreal police. Although his superiors would not grant him an unpaid leave of absence, he went to St Louis anyway under the banner of the Montreal Amateur Athletic Association, and on returning covered with glory, he was immediately rehired. He won his fame in the midst of what was then considered a “big circus,” during which various groups, Sioux, Patagonians, Pygmies, and Moros among others, held their own games, dubbed Anthropological Day. At St Louis, as at Paris in 1900, the Olympic Games lost the esteem of their supporters and of the general public. The 1900 games had suffered from being linked with the universal exposition being held in the French capital; the same mistake was made in 1904, since the games were held in conjunction with the Louisiana Purchase exposition in St Louis. Moreover national and international events took the headlines in the summer of 1904. What with the presidential election campaign in the United States and interest in the Russo-Japanese War, which was at its height, the Olympic Games attracted little attention. Athletes from eight countries, or, according to some sources, eleven, took part in the St Louis games, including contestants from the United States and Canada. With more than 1,500 athletes (nearly half the total number), the Americans carried off 20 of the 21 medals awarded in track and field. Desmarteau alone succeeded in breaking this monopoly. Although not triumphal, his arrival back in Montreal was greeted with demonstrations of joy. La Presse described him as the “champion of the universe, whose comrades at Station 5, on Rue Chenneville, were getting ready for a great show . . . to celebrate his victorious return.” The following year he achieved another success in the Montreal police field events; on 26 July 1905 he set a new world record for the 56-pound high-throw, reaching 15 feet 9 inches. A few months later, at the age of 32, Étienne Desmarteau died in Montreal, where he was training for a competition. He was probably a victim of typhoid fever. In the period leading up to the 1976 Olympic Games, which were held there, the city honoured him by giving the name of Étienne Desmarteau to an athletic centre and to a park in Rosemont previously known as Drummond Park. He had already been elected to Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1955. "From another newspaper" A district, a park and a sports arena in Montréal have been named after him; the Étienne Desmarteau Centre was used as a venue for basketball during the 1976 Summer Olympics. The District d'Étienne Desmarteau is part of the borough of Rosemont–La Petite-Patrie. In November 2008 Marc-André Gadoury was named candidate for Projet Montreal in the District d'Étienne Desmarteau for the November 2009 election. |

ÉTIENNE DESMARTEAU CANADA’S FIRST OLYMPIC GOLD MEDALIST by Glynn A. Leyshon

In the annals of the modern Olympic Games, the first Canadian to win an Olympic gold medal was George Orton.

Orton, from Strathroy, Ontario, was a student at the University of Pennsylvania at the time he conquered all in the 2,500

metre steeplechase at Paris in 1900. Orton, however, ran on the U.S. team, and despite his citizenship, the victory was

credited to the U.S.A. The Olympic marathon in the 1904 Olympics in St. Louis was won by Thomas Hicks who was also reported

to be a Canadian although he ran in U.S. colors [Cambridgeport YMCA, Cambridge, Massachusetts]. The Montreal Star of the

time claimed he was from Fredericton, New Brunswick, and that he trained on the road between Peniac and Marysville,

New Brunswick. Hicks, who was born in England, at this time lived in Cambridge and his athletic laurels were claimed by

the U.S. once again. It remained, therefore, for one Étienne Desmarteau to be acclaimed as the first officially recognized

Canadian to win an Olympic gold medal in track & field athletics. [Editor’s Note: The Canadian lacrosse team, The

Shamrocks, won a gold medal in lacrosse in 1904 almost two months prior to Desmarteau’s gold medal.] This he accomplished

in the 56- pound weight throw with a distance of 34’ 4¾” (10.48) at the St. Louis Games in 1904.

The event and the Games in general in 1904 were unusual by today’s precise and exacting athletic standards. The 56-pound weight itself, no longer used in any major competition, begs for an explanation. Why not a round number like 50 pounds or 60 pounds? The size apparently derived from the English measure in which a stone equalled 14 pounds. A so-called hundred-weight by that measure actually did not weigh a hundred pounds, but 112 pounds, or eight stone [50.91 kg.]; a half-hundred-weight, therefore, was 56 pounds [25.45 kg.] or four stone. The delivery of the stone was freestyle. Get it as far as possible any way possible short of rolling it. The event was marked by a lack of grace. Often the burly contestants stood facing away from the direction of throwing, swing the weight between their legs, and with a grunt, arched backward flinging the stone overhead. Another method was to spin as do modern throwers of the discus and hammer. It was also possible to cast the stone, with its attached handle, using an unlimited run and follow. The latter approach gave the object more momentum, and the throw was measured from the point of release wherever that was judged to be. Unlimited run and follow was a definite advantage since the thrower could run or stumble several yards after release. Not satisfied with throwing for distance, the contestant also often vied for the title of highest thrower. An old rule book lists the regulations for this outdated sport as follows: 1. A wooden disc 3 feet in diameter must be suspended horizontally in the air. 2. The judge will decide at what height the disc will be to start. 3. Throwing will be done from inside a circle 7 feet in diameter. 4. To count, a throw must hit the disc. The thrower must remain inside the circle until the hammer hits the disc. 5. The method of competition shall be the same as for the high jump, i.e., three attempts at each height. Desmarteau was as adept at throwing for height as he was at the throw for distance. In Ottawa in August of 1904, a month before his victory at the Olympics, he managed a heave for height of 14’8” [4.48] after setting a Canadian record in the distance event with a throw of 36’6½” [11.14]. In the same meet he also won all the remaining throw events: the 16-pound hammer, the discus, and the 16-pound shot put for a total of five firsts. The throw for height was not contested at the St. Louis Olympics, and also there was the imposition of a restraining rule on the throw for distance. The weight had to be thrown from within a 7 foot [2.13] circle for the first time. Unlimited run and follow, therefore, would not be possible. Since the American champion, “Genial” John Flanagan had recently established a world record of 40’2” [12.24] using this method, he probably felt the restrictionmore than Desmarteau. The Olympic Games of 1904 were an odd mixture of events and spectacle. Originally the International Olympic Committee awarded the Games to Chicago, but they were later moved to St. Louis as part of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition of 1904. The Olympic Games became part sideshow as a result and every type of bizarre contest carried on from May through to November of that year was labelled an Olympic event. 309 of them and each of them was provided with Olympic medals. There were an astonishing One can only speculate as to how, for example, the winners of the Olympic mud fight were adjudged. Anthropological days, were contested between native peoples, and in one of these, pygmies and North American Indians dodged and engaged in a mud fight. These events were billed as a kind of aboriginal Olympics and contributed to the sideshow atmosphere which continued to cast a shadow over the real athletic contest. To further confuse things, an elaborate handicap system made an understanding of the results of legitimate and recognized events very difficult. A Toronto paper The Globe, for example, recording the events in St. Louis indicated that the 56-pound weight throw was won by A[lbert] Johnson of the U.S. with a throw of 25’8” [7.82] and a handicap of 11 feet [3.36]. Desmarteau was listed as second with a throw of 34’4¾” [10.49] and a handicap of 6 feet [l.84]. The official report of the Games in the Montreal Star of 2 September 1904 listed the event as throwing the 56-pound weight (handicap) - Albert Johnson [Central YMCA, St.Louis] won 35’3” [10.74], with E. Desmarteau [Montreal] listed as 4th, with 34’10¾” actual throwing and a 6 inch [15.2 cm.] handicap. Into this confused maelstrom of athletic contest and sideshow events came French-Canadian strongman and Montreal cop, Étienne Desmarteau. There had been a long tradition of French-Canadian strong men, Louis Cyr being the most prominent and Desmarteau lived up to it nicely, although he was not a huge man by any means. He weighed just over 200 pounds and stood about 6 feet tall. The original family name was Birtz and they first settled in Boucherville in 1757. The first colonist, Étienne Birtz, was said to have herculean strength, and was a blacksmith. His sign advertising his trade bore crossed hammers which earned him the nickname “Desmarteaux” (literally, “Mr. Hammer”). With the final “x” chopped away this eventually became the family name, and seemed a fitting one for the 1904 Étienne who threw the hammer in competition. He had three brothers: Elezar, Frederic, and Zachary. The latter often finished a close second to Étienne in competition, and he accompanied him to St. Louis. Desmarteau’s preparation for the Olympic Games was not elaborate nor extensive by today’s standards. It took the form mainly of competition in meets over a period of years. There was no supplementary weight training, no sport psychologist in attendance, and no dietician. Simply throw the stone as often as possible. Desmarteau, according to a Comité d’Organisation des Jeux Olympiques (COJO) release of 1976, worked for a period of time for the Canadian Pacific Foundry (a holdover to his smithy roots, no doubt) and then, at age 28, joined the Montreal Police Force in 1901. It was then that he came into his own as an athlete representing the Palestre Nationale de Montreal as well as the Montreal Police Athletic Association. He won Dominion titles in 1902, 1903, and 1904, but it is unclear in what exact events he held these championships [Editor’s Note: he was Canadian champion in 1902-03 in the 56-pound weight but is not listed with any other Canadian championships in Canadian Athletics 1839-1992 by Bill McNulty and Ted Radcliffe]. He competed extensively in eastern Canada and the U.S.A. in Police Games and in open competition. While the police force was happy to have the modest, amiable strong man throw things on weekends, giving him leave to go all the way to St. Louis for a week to two was out of the question, Olympics or no Olympics. If he left without permission, it would be a breach of discipline and he would be dismissed. His request for a leave of absence was refused. For Desmarteau it was a heart-rending decision. Should he give up his job to compete in St. Louis, or retain the security of a good position and allow his chief rival, John Flanagan, a New York cop, to win unopposed? It was not an easy decision but Desmarteau chose to go to the Games, and take a chance on his future. His job was lost. The famous Montreal Amateur Athletic Association helped to sponsor him when he turned to them for assistance, and, in return, he wore their winged-wheeler crest in the contest. (All the athletes in the Games wore their individual club colors, not the national symbols of their respective countries.) The amount of the sponsorship was unspecified, but a return excursion fare by train, Montreal to St. Louis, was $19.50. By way of further comparison, the Prime Minister, Sir Wilfred Laurier, was paid a salary of $8,000.00 per annum in 1904. It did not take a king’s ransom to support an athlete for a week or two, In St. Louis, “Frenchy” as Desmarteau was known to the milling crowds of American athletes, stood out as one of the few foreigners in the entire competition. Most countries ignored the Games. There were no entries, for example, from either Britain or France. [Editor’s Note: There were Irish competitors, however, and Albert Corey, who finished second in the marathon representing the Chicago Athletic Association, was still a French citizen.] It was an All-American show. Of the 22 track & field events, the Americans won 21 and in many cases swept the first three places. Desmarteau was the spoiler of a clean sweep for the U.S. in track & field. He was not only Canada’s first Olympic gold medalist, he was the only non-American to win an event in athletics. The weather for the Games was extremely hot and that sapped the strength of the big men. Desmarteau, however, had the added burden of his decision and wrangling that had preceded his departure. Dr. J. P. Gadbois, writing in La Presse on 2 September 1904, noted that: “ The American [Flanagan] had a host of advantages on his side: thanks to his team, he had reached St. Louis without an and enjoyed all the benefits of a rich and powerf difficulty, was well-coached, ul organization. Flanagan had not spent the previous weeks tom between hope and disappointment; he did not have to suffer a refusal before being given the chance to compete in the Games. Flanagan had everything on his side except the power to beat Desmarteau: the American had the experience, the ability, and the coaching, but our champion had the strength characteristic of the athletes of our race.” Although Desmarteau had defeated Flanagan at the AAU Indoor Championships in New York two years previously, the big Irish-American was the favorite in St. Louis. A phalanx of American big men were also contenders including Ralph Rose of California (eventually 6th of 6 competitors) and two others, Jim Mitchel (3rd place) and Charles Hennemann (4th place). John Flanagan had won the 16-pound hammer throw in the 1900 Olympics in Paris, and had already duplicated the feat here in St. Louis. (A curious aside is that his brother, Tom Flanagan, was a hotel keeper in Toronto, and became the manager of the famous Canadian marathoner, Tom Longboat.) Flanagan, in addition, held the world in the 56-pound throw, albeit under a different set of rules (unlimited run and follow). He was a formidable opponent competing on friendly grounds. Of the American “whales,” he was the pick. The competition began. Rose threw first and fouled, being unused to the restraining circle. Desmarteau was next and, using a single spin, launched the stone in what was to prove the winning distance, 34’4¾” [10.49]. scant inch behind. Flanagan’s effort was 33’4” [10.16] with Mitchel a The trio plus Hennemann advanced to the finals. The finalists had three more throws in St. Louis. As the day grew hotter, none had much hope of bettering earlier marks. Under the rules, the best throw of the day was to count regardless of whether it was made in the preliminaries or the finals. Desmarteau, Mitchel, and Flanagan could not better their qualifying marks; Flanagan actually had five fouls and only the one fair throw. winner. When no one could better Étienne’s first prodigious throw, it stood as the Canada had its first official Olympic gold medal in track & field athletics. After the final stone was cast Desmarteau was paraded around the field on the shoulder of the others, both Canadian and American. The supporting cast included a small contingent wearing the winged-wheeler crest of the Montreal AAA who had competed in others events, brother Zachary Desmarteau, half-miler John Peck, miler Peter Deer, and sprinter Frank Lukeman. The New York Times, commenting on the competition, was less than gracious: “The results of the 56-pound weight throw proved a disappointment. It was confidently expected that Flanagan of the Greater New York Irish Athletic Association would break the Olympic record and possibly the world record. The New Yorker was in poor form and not only did he fail to surpass the records made by himself at former meets, but he was beaten by a clean foot by E. Desmarteau of Montreal The latter’s best throw was 34’4¾”, 2 feet below Flanagan’s Olympic record.” [Editor’s Note: This is incorrect. The event had never been held before at the Olympics.] No mention was made of conditions or of the new rule requiring the stone to be delivered from within a circle. The Montreal paper Le Samedi cast the victory in a kinder light: “Le constable Étienne Desmarteau de Montreal, l’un des concurrants dans les jeux Olympiques a triomphe de la fine fleur des athletes Americaines et emporte la titre de champion dans la concourse pour lancer le poids de 56 livres. Il a battu le redoutable Flanagan par un pied, affermant d’une façon incontestable sa superiorité sur le ancien champion. ” The triumphant homecoming usually awarded such heroes as Desmarteau appeared that it would be marred by the fact that Desmarteau had no job to return to. Or would it? There is nothing like a spectacular victory to affect the memory of bad events. Somehow, Étienne’s dismissal notice was lost. A bit of fast bureaucratic side-stepping and station number five, Rue Chenneville of the Montreal Police Department was decked out to welcome the conquering hero who would, of course, be ready to resume his duties in a few days. There were many eulogistic speeches at the reception and Lieutenant Morin presented Desmarteau with an illuminated address in memory of his feat. It read in part: “Your brilliant success, your dazzling victory over some of the world’s best athletes have brought you honor and glory in the eyes of those who live south of the border. The many laurels you have earned so gloriously have brought joy to all of Canada and particular honour to French Canada, and consequently to your comrades on the police force of the Dominion’s greatest city.” Desmarteau continued to compete, but disaster loomed. After a meet in 1905 at which he set a new record for the throw for height with 15’1l” [4.86], he came down with a fever. The exact diagnosis is unclear but speculation was that it was typhoid fever. Within a few days, Étienne Desmarteau was dead at age 32. The 56-pound weight throw was discontinued as an Olympic event, except for a brief renaissance at the 1920 Olympics, and then dropped again never to reappear. Forms of the event in which a heavy stone, often without a handle, is cast as far as possible, still exist in various forms of Highland Games to this day. Étienne Desmarteau was inducted into Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame in 1955 under the automatic induction criterion, i.e., anyone winning a gold medal in the Olympics is an automatic inductee. It was 51 years after his brief appearance on the world stage. He was a bachelor at his death and died without issue. |

Elizabeth Birtz et Francis Thill |

|

|

|

Birth: 1829, Luxembourg Death: Jan. 19, 1890 Williamsburg Kings County (Brooklyn) New York USA 1880-06-01 Census, City of Brooklyn, Kings Co. 68 Wilson St. Francis Thill, 50, glass manufacturer, b. Holland Elizabeth, 43, b. Belgium Margaret, 22 Elizabeth, 19 Harry, 18, Clerk in Store Annie, 16 Frank, 15, Clerk in Store Nicholas, 13 Mamie, 11 John, 9 Charley, 7 Albert, 5 Cecillia, 4 |